Alabama Power, residents meet about coal ash pond

Published 9:27 am Thursday, July 9, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By SCOTT MIMS / Staff Writer

WILSONVILLE — A public meeting was held Monday night, July 6, at Wilsonville Baptist Church regarding the coal ash pond at E.C. Gaston Steam Plant on Lay Lake.

Several residents, including representatives from Coosa Riverkeeper, peacefully protested outside the meeting, carrying signs in support of moving the coal ash to a different location to prevent future groundwater contamination at the plant site.

“Move your ash off our river,” read one sign. “Stop poisoning our ground water,” read another with an illustration of a skull and crossbones.

Coal ash is the waste that is left over after coal is burned to produce electricity. It contains toxic heavy metals such as mercury, lead and arsenic. Wilsonville’s coal ash pond was established in the 1960s prior to federal regulations requiring such ponds to be lined.

Alabama Power is currently looking at plans to permanently enclose the pond, which is an alternative method to moving the material. The next step in the plan is to obtain permits from the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM), which could take place within the next year.

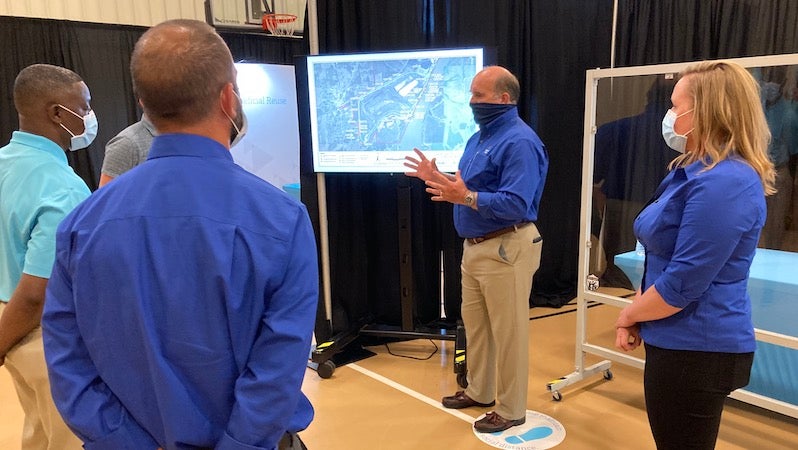

At Monday’s meeting, Alabama Power set up several booths featuring visual aides to demonstrate the history of the site and the company’s plan to enclose the coal ash pond. The meeting was conducted with plexiglass safety shields and social distancing measures in place due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve stopped using the ash ponds at all our plants, we’ve installed new water treatment facilities in places where we’re still using coal, like at Gaston we use both natural gas and coal,” said Michael Sznajderman, manager, corporate information with Alabama Power. “We’ve moved to a dry ash handling system that’s been installed and now we’re recycling most of the ash that is still being produced where we’re producing it.”

Sznajderman said that based on intensive study and input from third-party experts, the company has determined the best process at its plants is to dewater the ponds, consolidate the material into a smaller footprint, add engineered structures around the closed and dewatered ponds, and cap them with an impermeable cap. Monitoring wells have also been added around the facilities, he said.

Sznajderman cited the Mobile Bay National Estuary Program as a third-party resource for information about coal ash, whose website is Mobilebaynep.com. There is information on the site about the trade-offs between capping in place versus transporting coal ash.

“We’ve determined using third-party experts as well that the safest, best plan is to close these facilities on site where we can monitor them on site rather than, some others would rather have us move this material to another location, which would extend the time that it takes to safely close these places, and of course you also raise the risk of moving this material through communities for a period of decades because you’re talking about 10, 15, 20 in some cases up to 30 years to move this material to another location,” Sznajderman added.

E.C. Gaston Plant Manager Brian Heinfeld agreed.

“I’ve raised kids here, and they still live fairly close by. We’ve been on the rivers, we’ve fished and swam, we do all that, so I care about it as much as anybody. I live in Shelby County, I drink the water from Shelby County. I want it to be as clean as possible,” Heinfeld said. “From what I’ve seen, this to me is the best for everybody and the surrounding area, it’s best for the county and the state so I feel really good about what we’re planning to do.”

Heinfeld did say he was willing to listen to those who disagree with the plan.

“My feeling is we can talk about it. Let’s talk about it and talk about the facts,” he said.

Steven Dudley with Coosa Riverkeeper is among those who feel the coal ash should be removed from the site.

“We’ve seen at the Gadsden plant that they’ve chosen to cap in place, and last year or their last monitoring period, the results show that they are still in violation of their permit,” Dudley said. “They make the argument that cap in place can solve all these problems with groundwater contamination but at the Gaston plant, we see that that’s simply not the case. They’re currently contaminating groundwater with harmful heavy metals, which several of these contaminants pose adverse health effects on people and they can ultimately hurt the ecosystem itself.”

Dudley wanted a virtual option to Monday’s meeting, and he said he was hoping for a town hall-type setting with a panel of people taking questions from residents.

“That’s kind of what we were hoping for, but that’s not what we saw here today,” he said. “We were kind of disappointed to see the turnout today. We were hoping that there would be more interaction and more ideas interchanged between the power company and the community.”

Also present was Keith Johnston, managing attorney with Southern Environmental Law Center of Birmingham. He cited examples of coal ash removal at plants in other states as backup for the pro-removal argument.

“In South Carolina you’ve got utilities that are voluntarily excavating and removing…in Tennessee you have at least two sites, and in Georgia, Georgia Power is removing all their coastal sites,” Johnston said. “The argument that it can’t be done or it takes too much time, utilities are proving that they can do it. It’s a question of do they want to do it, and do they want to spend money to do it, and Alabama Power is choosing not to.”

Wilsonville Mayor Lee McCarty also weighed in on the issue, saying he believes that if capped in place, the coal ash pond will continue to leak.

“Nobody can ever give me an answer, because it never works. It just makes no common sense,” he said.

Patrick Cagle, president of the Alabama Coal Association, was also in attendance and shared comments in support of Alabama Power’s plan.

“The plans for safely closing and sealing in place the CCR impoundments at Alabama Power’s Gaston Steam Plant exceed the federal requirements established by the Obama Administration’s EPA,” Cagle said. “These regulations were developed with extensive public input and the concerns currently being expressed by local environmental groups have already been considered, and ultimately rejected, by both the Obama and Trump administrations. The bottom line is that dewatering, consolidating and safely sealing the CCR stored at Gaston is the most efficient way to mitigate the risk posed by the storage of CCR in an open impoundment.”