PROFILE: National Weather Service: Chasing mother nature

Published 4:40 pm Monday, February 24, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By SCOTT MIMS / Staff Writer

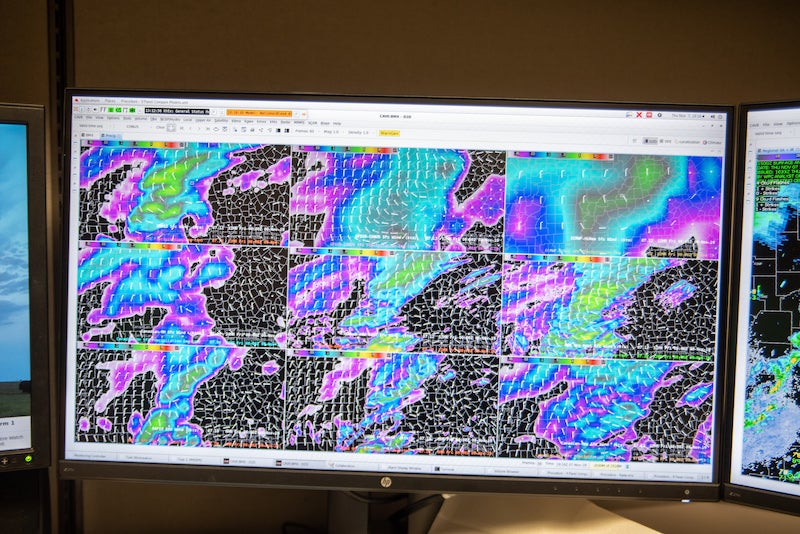

A wall full of monitors flickers as blip after blip of information crosses them to greet the eyes of meteorologists. Some screens display weather information, others show news or an infomercial. But none ever turn off, even at 1 a.m. Such is life at the National Weather Service (NWS) Birmingham headquarters right off the Shelby County Airport exit in Calera.

This night is a relatively quiet one, but had the slightest possibility of a snow flurry been in the forecast—or even hinted at on Twitter by some self-proclaimed weather guru—the phones might be ringing off the hook. “Our daughter is getting married four weeks from now. What’s the forecast?” a caller might ask. “Do I need to go to the grocery store now or wait till tomorrow?” another might pose.

The newest weather models often come in between midnight and 1 a.m. with a fresh set of data. In that time frame you’ll find meteorologist Nathan Owen poring over the reports, comparing local data with that from other locations, sometimes for hours on end. It takes a cold front about six hours to travel from west to east Alabama, and during that time Owen is hyper-focused. He calls times like this “short-fuse events.”

“You haven’t reached for a glass of water, you haven’t gone to the bathroom, you haven’t done anything because you’ve been waiting for that next bit of information,” he says. “We get a new radar scan almost every minute. It’s all about getting the forecast 100 percent correct or as correct as we can.”

New information could mean he has to issue a warning. Or, it could mean nothing. Before he knows it, his shift is nearly over. Sometimes his “lunch” is at 3 a.m., others he never gets to eating or even taking a break.

Regardless of meal time, every day at 5 a.m. and 5 p.m., weather balloons are released into the sky just as they are from NWS stations across the globe. Once airborne they record atmospheric conditions like temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, wind direction and speed. All this data then is ingested into the supercomputers, which in turn start running and crunching the numbers—a cycle that repeats every 12 hours.

Approaching danger

Other parts of the day are far less like clockwork as certain signatures on the radar screen can stop a meteorologist in his tracks. What indicates real danger is a debris signature from a tornado—which is caused by debris in the air scattered by the storms. Some natural phenomena, such as birds taking flight from a wildlife refuge early in the morning, can resemble a debris signature. It’s when the imagery comes in conjunction with a hook-shaped weather radar signature as part of thunderstorms that Owen takes notice.

“Whenever you see it, you warn, but you kind of have to take a step back,” Owen says. “If the debris keeps getting bigger and bigger, you know it’s doing a lot of damage. That can be a humbling thing you can see on the computer screen, knowing what it means.”

In that moment, the NWS notifies emergency managers first. “If it’s heading toward a population center, that’s when our senses really get heightened,” fellow meteorologist Gerald Satterwhite says.

That said, if you want to catch a meteorologist at their busiest, just listen for the key word: snow. Meteorologist-In-Charge Chris Darden knows this all too well. “If there’s a forecast of winter weather, that’s probably when the public calls ramp up the most,” Darden says.

But if the chance of snow is still a week away, don’t take what the weatherman says as the gospel. “The forecast is always changing, and realizing that every weather event that comes through, it may not impact you,” Satterwhite says. “It may impact people 15 miles away. The next time it could impact your neighborhood.”

Regardless of the forecast on a given day, everyone from emergency professionals to football announcers live by information from NWS. Case in point: Darden recalls a UAB versus Rice football game taking place alongside a soccer game. Thanks to information from NWS, an announcement was made for attendees to take shelter before lighting strikes began. “Any one of those strikes could have posed a danger to people on the field, the people in the stands,” Owen says. “The forecast doesn’t stop with us at the computer. We have to take that and message it and key in on things that would be important to the average person.”

Even incidents that aren’t directly weather-related—like a train derailment or an issue with a pipeline—could turn disastrous without weather updates. “We need to make sure we’re giving them micro-detailed information because a wind shift could be disastrous for first responders,” Darden says.

Even on quiet days, weather information is vital. Pilots taking off and landing at airports in Birmingham, Shelby County, Tuscaloosa, Anniston, Talladega, Montgomery and Troy all rely on up-to-the-minute information from the Calera station regarding cloud cover and wind direction. If there is no precipitation, fire threats arise.

Once a construction crew was working on a major project in downtown Wetumpka. The crew foreman who was monitoring the weather got an alert on his phone. Because of this, the lives of the crew were potentially saved from an approaching tornado. “He was incredibly appreciative (because), number one, obviously the liability of having a crew out there, (and) number two, his crew was his family,” Darden recalls.

Getting the warning out

Technology is ever shaping how Darden and his colleagues do their jobs too. In 2007, NWS transitioned from a county-based warning system to a polygon-based system—a term arguably popularized by ABC 33/40 meteorologist James Spann. Before, severe weather anywhere in Shelby County would result in a warning being issued for the entire county. Now, meteorologists can tailor the warning to the specific area where the event is happening.

While technology is helpful, though, Darden indicates there is no substitute for common sense.

“It’s just a matter of people having a plan,” he says. “It’s one thing to want to take action, but do you know how to take action? Are you able to get to a safe location? Do you have a safety kit? The warning lead time might be 10 minutes, but if it takes you five minutes to get the information, that leaves you only five minutes.”

Then there are the times when Mother Nature seems to make a fool of science. Darden recalls an incident when he was an intern in Burlington, Vermont. On a spring night, a cold front was dumping cold rain that suddenly changed to a sheet of white. It started snowing when the surface temperature was still 51 degrees.

“They say it’s part science and part art, but it is. That’s the human side of forecasting,” he says. “Otherwise you could just flip a switch and have the computer models generate a forecast.”

Humans are also key to spreading weather information to the public. “For the one person we can reach, (someone on social media or TV) can reach 100,” Darden explains. “Yes, the people got alerts on their phone, but the local media person they know, they helped personalize to them that something was coming.”

And while the blips on the NWS monitor are vital, so is communication. “Our last word is service,” Darden says. “What we do inside the building probably doesn’t matter a whole lot if the people in the public don’t know what to do with our messages. Really, our job is to protect life and property, and that’s how we can mitigate a lost life from weather events. Our mission is saving lives.”