Bates recalls early days in Shelby County

Published 10:39 am Monday, March 26, 2012

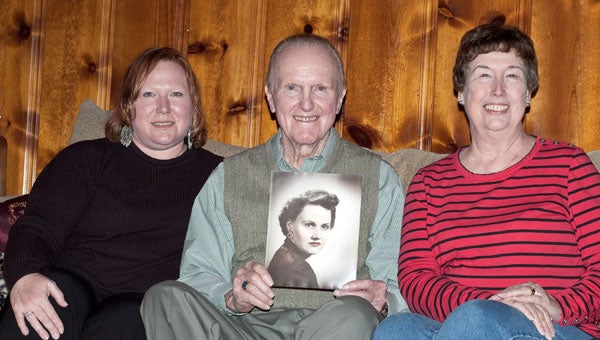

‘Red’ Bates met his wife, Ruby Irene, when she was 16 and he was 17. Red and Irene, who now live in Bessemer, celebrated their 67th anniversary in 2011. Irene was not present the day this photo was taken when he visited with Shannon Cowart and her mother, Elsie Cowart. (Contributed)

By LAURA BROOKHART / Community Columnist

Houston “Red” Bates, with a head full of red curls that his mama didn’t cut until he started school, grew up in Helena in the 1930s.

He is the great uncle of Shannon Cowart, whose memories appeared in this column on Feb. 29.

One of three remaining living siblings out of 13, Bates said the family lived in the Roebuck community when he was born in 1926. There, his father, John Bates, worked at the mine, and he remembers April 1933 when the big tornado came through.

“We all went down to the storm pit. It was all my daddy could do to hold the door shut.”

But around their house, only trees were blown over. Bates also recalls a baseball field near their house where his father played on a team. The family attended a Baptist church down Coalmont Road near a creek where baptisms were held.

“We didn’t have much, not much food and no toys, no radio. We played outside all day. We climbed trees and jumped from limb to limb like monkeys. We made slingshots and shot at birds. I remember I would go out and eat from the mulberry bushes when they were ripe.

“We knew one black family at Coalmont and they had a cow. I would hang around and that lady would invite me in to eat cornbread and buttermilk.”

As the Depression wore on and the Roebuck mine shut down, the Bates family, three months in arrears on their $5 monthly rent, was evicted. In an emotional voice, Bates recalled they really had no place to go. The county sheriff came out and insisted the furniture be moved out of the house, into the yard.

“My sister Lynda (Cowart’s great-grandmother and second eldest who was a surrogate mother to the younger siblings) was fighting them all the way, but it did no good.”

Fortunately, a house in nearby Red Ash community was available. They carried their furniture up the railroad bed to their new home. Red Ash was in the back of today’s Old Cahaba subdivision.

There, Bates recalled, the family’s shotgun house had three rooms, two fireplaces and a wood stove for cooking. The house had shutters that could be closed at night — there were no glass windowpanes. His youngest sister, Loretta, was born there.

“We all slept in three beds, turned different ways — someone’s foot would be in the next person’s mouth,” he said. “We had no water, no electricity. We used kerosene lamps and had an outhouse about 80 feet away. About a quarter mile away and down a steep hill was a spring where we collected buckets of drinking water and where we took our clothes to be washed weekly in a big iron pot. I built the fire and my sisters boiled and boiled them, probably with lye, and hung them on the bushes to dry.”

‘Big John’ Bates eventually became the foreman at Red Ash mine.

“When I was young, I rode the school bus to the Helena School and when I turned 16, they hired me to drive the bus.”

Bates had learned to drive at age 12 in his oldest brother James’s Plymouth that had wooden spokes and wheels. The car had to be parked frequently in the creek, so that the wooden wheels would swell up enough to be driven.

Laura Brookhart can be reached by email at labro16@yahoo.com.