Remembering Alabaster’s black history

Published 3:11 pm Tuesday, February 18, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

ALABASTER – Every year, the month of February signifies Black History Month and all Americans are encouraged to remember, learn about and celebrate African American history, culture and achievements.

In Alabama, the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement, there’s a lot to reflect on. Prominent African Americans like Dr. Martin L. King Jr. and Rosa Parks were and still are the faces of the Civil Rights movement, but it’s also important to note that many African Americans in small Alabama towns were also working hard to improve their lot in life.

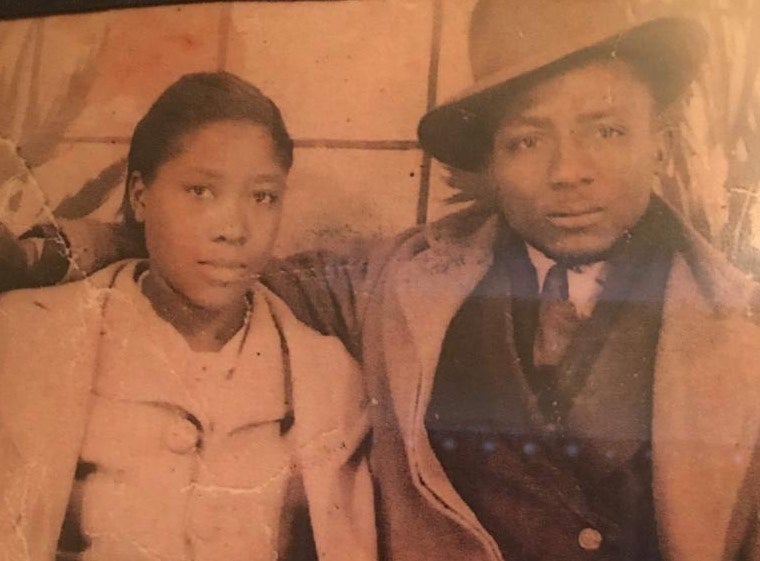

In Alabaster, the legacies of several prominent black families have been kept alive by their descendants. Their stories have been told and retold in hopes that their struggles and triumphs will inspire today’s generations. Adrian Rhinehart, an Alabaster native who now lives in Calera, said information about his great grandparents Maynard and Alene Cohill and his great uncle and aunt Paul Cohill Sr. and Annie Cohill have been passed down to him throughout his life.

“We have a lot of inspiring people who grew up in the same place that we grew up,” Rhinehart said. “I just don’t want people to forget our history and our roots.”

Several roads and even a park in Alabaster bear the names of African Americans who were inspirational within the city. Those streets are Cohill Drive, Dilcy Daniel Drive, Arrington Avenue, Ferguson Lane and then there’s Abbey Wooley Park.

Off Simmsville Road sits Cohill Drive. It was named after Maynard and Alene Cohill and Annie and Paul Cohill Sr. Originally from Vincent, Maynard moved to Alabaster in the 1940’s where he got a job with a railroad company and then purchased land to live on from Abbey Wooley, the woman for whom Abbey Wooley Park is named.

Not only did Wooley, who lived to be 104 years old, sell some of her land to local residents but she also donated portions of it. Mount Olive Baptist Church sits on land that was donated by Wooley, and she loved the city of Alabaster so much that she donated land to the city for a park to be built in her name. She also sold other portions of the land for public housing projects to be built.

Maynard soon sold a portion of his land to his brother Paul who then moved his family to Alabaster. Paul opened a small store in the community and his wife Annie served as the kitchen director at Liberty Missionary Baptist Church.

Maynard’s wife Alene worked several years cleaning and cooking for the city’s well-known doctor, Dr. Frank Abernathy, according to Rhinehart. Maynard became a deacon at the Liberty Missionary Baptist Church and Alene became a member of the Starlight Chapter No. 81 Order of the Eastern Star, a Freemason organization with stated goals of charity, fraternity, education and science.

Rhinehart said the Cohill family eventually became known in the community as “upper class black people.” Maynard and Alene were the first in the community to own a television or have running water inside their home, Rhinehart said. Elders in the community recall being invited to Maynard’s home to watch boxing matches and Major League Baseball games. According to Rhinehart, he sat his TV on the porch so neighbors could all gather around to watch.

Serving alongside Maynard as a deacon at Liberty was his good friend Willie B. Arrington, who served Ward 1 on the Alabaster City Council from 1981-1992. Before being elected to the City Council, Arrington served on the city’s adjustment board, water and gas board and personnel board. Later in life he served on the Alabaster Water Board. His wife Corene worked for many years at Shelby Baptist Medical Center.

In 2009, two years before his death at age 94, Alabaster renamed the former Fifth Avenue Southeast off Shelby County 11 to Arrington Avenue.

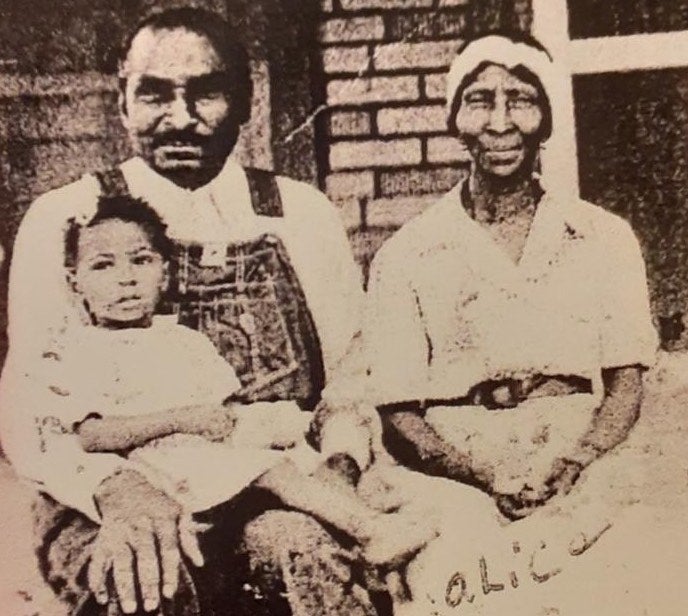

Just off Cohill Drive sits Ferguson Lane, named for Jim and Alice Ferguson. The Fergusons, who were originally from Marengo County, settled in Alabaster and became well-known for being among the black families that owned a substantial amount of land in the community.

“I recall my grandfather telling me how Mrs. Alice Ferguson didn’t need a land surveyor because she knew everything about where their land started and stopped,” Rhinehart said.

The Ferguson family went on to build New Life Outreach Ministries and Caffey Cemetery on their property.

Dilcy Daniels, the granddaughter of slaves, made her mark on the community with the founding of Emmanuel Temple Holiness Church in 1945. During a trip to Ohio to visit relatives, Rhinehart said Daniels had an experience with God that led her to start her own church when she returned home to Alabama. Today, Dilcy Daniel Drive sits off Simmsville Road.

“I can remember her very well as being my next-door neighbor,” Rhinehart said. “I would go sit on her porch and talk with her. She lived to be 107 years old.”

Although these families weren’t leaders of a national movement, they were revolutionary and impactful in their own rights. In Alabaster, they helped change the perception about the kinds of lives black people were able to live.

These families coped and found ways to thrive under the racist societal constraints of segregation and Jim Crow laws. They grew to become civic leaders, entrepreneurs and beacons of hope and inspiration for their community.

“They worked so hard to have something to call their own and that is just so impressive to me,” Rhinehart said. “It motivates me to continue to work hard and do what’s right.”

More Alabaster Reporter