PROFILE: Neil Bailey: Giver of Second Chances

Published 4:33 pm Monday, March 4, 2019

By ALEC ETHEREDGE

Photos by Keith McCoy

Standing at the door to the counselor’s office at the DAY Program, a young girl was contemplating taking her life. She’d tried to drop out of school in the eighth grade, just shy of the age her mother was when she gave birth to her at 14. Judge Patti Smith, who was the juvenile court judge at the time, wouldn’t stand for her dropping out though. Instead, she gave her a chance at life by sending her to the DAY (Developing Alabama Youth) program.

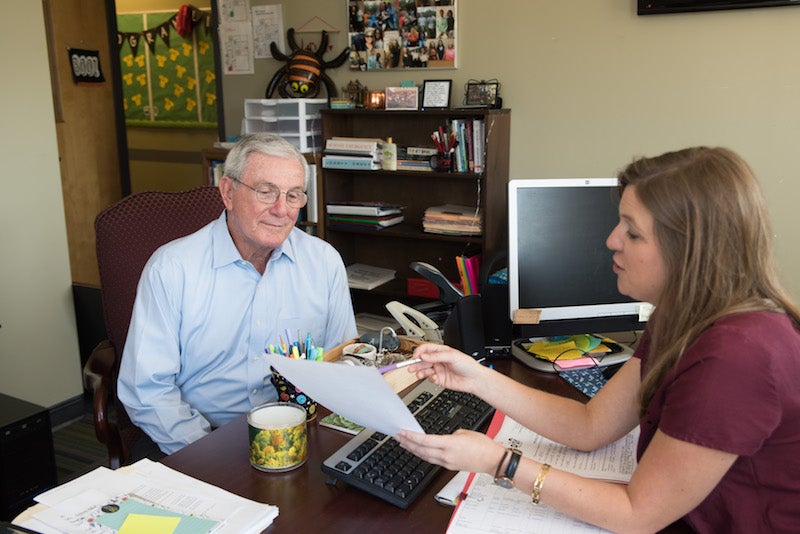

While a counselor was able to talk her out of taking her life, it was clear this girl’s struggles were complex. And that’s when she met Neil Bailey. “I told my wife at the time that we needed to take her in and help her,” says Bailey, the DAY Program treasurer. “To see what she went on to accomplish in life was incredible. After regaining belief in herself, she went on to graduate from Chelsea and I gave her a part-time job, but she wanted more out of life.”

This girl ended up getting a two-year nursing degree at Jefferson State and a job at Vanderbilt University—one of eight to get it out of 400 applicants. “She basically became our daughter,” Bailey says. “I was so proud of her and she went on to tell her story about the DAY Program statewide, which extended its impact to others.”

And it didn’t end there. She went on to get her four-year degree from Alabama and now has two daughters herself. “She could have dropped out of school in the eighth grade, and there is no telling the trouble she would be in or if she would even be alive,” Bailey says. “It’s not only incredible to see the impact the entire school had on her and many others, but to see her grow into this amazing young lady.”

It’s stories like this that Bailey’s life now revolves around, through the DAY Program as well as the Alabaster and Pelham YMCAs.

Unexpected Journeys

And these stories are ones that are not all that different from his own. After his parents divorced when he was 7, Bailey and his siblings were “at church every time doors were open.” “We went three times a week and would wait on the side of the road for somebody to pick us up and take us each day because of how poor we were,” he recalls.

He later sought that family like environment through Boy Scouts, hoping to build an extension of that family feeling. “Other people I was friends with didn’t join and ended up dead from drugs and other things,” Bailey says. “There is no telling where I would have wound up had it not been for their impact. It was because of Boy Scouts that I got to go to overnight sessions at the YMCA in Birmingham. That was the first pool I put my feet in besides the Cahaba River.”

At the time he only dreamed of playing major league baseball or coaching sports, but his time at the YMCA was laying the foundation for more dreams than he realized. “It’s interesting to see how dreams change over time and how unexpected journeys actually were a dream we didn’t know we would have,” he says today.

As the years went on, Bailey grew extremely close with the cause of the YMCA and its impact on families because his sister was a secretary for the Shelby County YMCA, which allowed him to help out whenever he liked. After working magic to expand the Pelham YMCA, Bailey turned to the Alabaster YMCA with the DAY Program’s future in mind too. At the time the Alabaster YMCA’s lease was running out. Almost simultaneously, like pieces to a puzzle falling into place, they learned a Masonic Lodge had just been given 39 acres of land it didn’t really need or know what to do with. “I understood that I could encourage the YMCA to acquire the extra property,” Bailey recounts. “They wanted it to be for a good purpose.”

The YMCA went on to buy all but a couple of the 39 acres, and with that they had a location to eventually expand to a bigger facility that would allow the DAY Program and YMCA to be housed in the same building. The DAY Program is now part of a joint venture with the YMCA that features 10,000 square feet of space and gives kids access to the entire second floor, as well as a ropes course, outdoor area, pool and more.

“The marriage of the DAY Program and the YMCA enabled the Y to do something they would have never been able to do otherwise,” Bailey says. “Without the DAY Program they would have had to have raised a couple million dollars. Because of other projects, the metro Y wasn’t going to do that any time soon, so we worked together to achieve our goals.”

There for the Kids

Through it all, the DAY Program has had the biggest impact on Bailey of anything he has done, he’ll tell you. And it will be the last board he resigns from. “I don’t think the DAY Program would have survived the past 35 years without his interest in the students’ welfare and his unwavering and dedicated support,” Judge Patti Smith says. “Now, we have these wonderful accommodations, and Neil is responsible for that.”

Since Smith, the former Shelby County Juvenile Court judge, started it in 1982, the program has provided services to at-risk adolescents and their families with an emphasis on academic remediation, behavior modification, training in coping and stress management skills, creating a goal-oriented foundation and employing life skills. “When I began my career as a Juvenile Court judge back in 1980, I recognized almost immediately there were some students who were falling through the cracks, and traditional educational programs just weren’t working,” Smith says. With the help of Alan Fulton, she convinced the superintendent that the DAY Program would change lives, which led to federal grants and funding from the Shelby County Board of Education.

Bailey wasn’t part of the DAY Program for the first four years, but eventually settled in on the board and helped it find a new home in the YMCA—a place that reminds him of his own story. “I see a lot of kids that remind me of myself, so it’s dear to my heart,” Bailey says. “I saw the immediate benefit of what the program could do for kids needing second and third chances after being raised in circumstances they didn’t have control over.”

For anyone living in Shelby County who as gone through probate court or has any sort of juvenile delinquency within the judicial system, the DAY Program offers the chance to get on the right path.

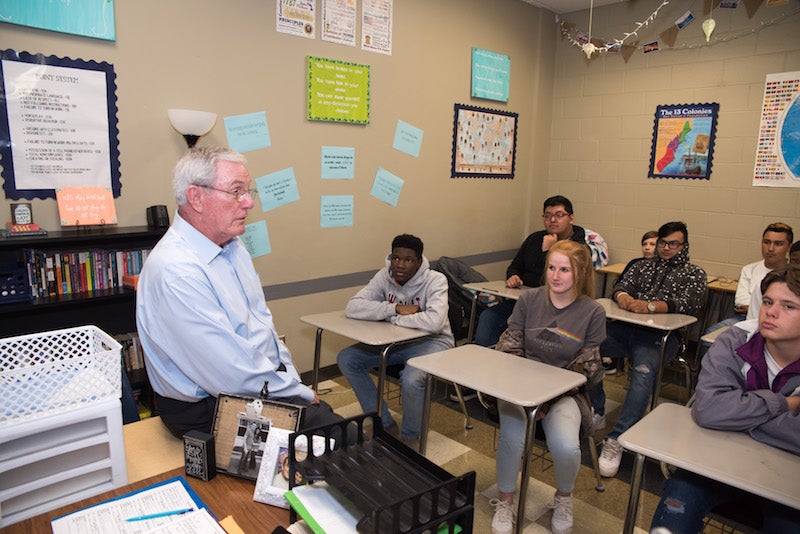

“The magical thing to me is that a lot of kids that come don’t want to be there,” Bailey says. “A lot of times, you’ll have parents check to see if they are still alive only so they can get a check. So it’s not surprising these kids don’t trust anybody or anything. That’s what the program seeks to change.

“Through counseling, they get a chance to catch up and grow and trust people again,” Bailey explains. “It gives them the confidence to get a GED or go back to school. When you finally see the light come on and those kids realize we are only there for them, to see how enthusiastic they become and realize they do have a chance, that is what makes the DAY Program worthwhile.”

Along the way, the program helps its participants gain not just academic confidence, but also social confidence. Often they don’t arrive because they are not smart or because they are in trouble, but because they have lost hope. To address these complexities, there is an instructor and counselor for every 15 students, and the program has a max of 70 students.

“I have a tremendous amount of respect for teachers and others that do public service work to make a difference in kids’ lives,” Bailey said. “To truly see their work pay off is something a lot may take for granted.”

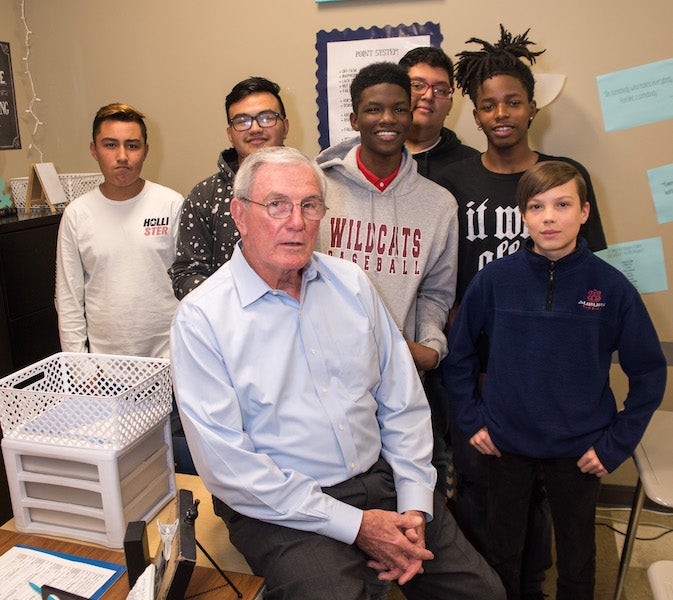

While the instruction is important, it’s also about getting the kids to believe, and that’s why Bailey and the board decided to start Honors Day. Starting at the beginning of the second semester, the students are told to lay out goals to achieve during the semester. At the end of the semester, they are rewarded for their work in a special awards program. “It sets a different mentality for kids that have never been rewarded for anything before,” Bailey says. “They are awards that just give the kids hope and confidence to aspire for more and know that they can achieve whatever they want.”

Talking about it takes Bailey back to the first ever Honors Day—one that will forever be embedded in his mind. “I remember Judge Smith standing at the small little podium calling out names,” he recalls. “Then she called out one kid’s name and called him up to get his trophy and certificate. He was smiling, and you could tell he was really proud. Smith was starting to go on to the next award before the student spoke. ‘Can I say something?’ he started. ‘I want to thank you, I ain’t ever been told I doing good about nothing.’ Then he stepped down.”

Bailey is visibly choked up recalling the moment. “That’s what it’s about,” he says. “I’ll never forget that moment… Once those kids see the future, they see that if they have that help, they can do things the right way.”