The evolution of communities

Published 2:37 pm Tuesday, July 12, 2011

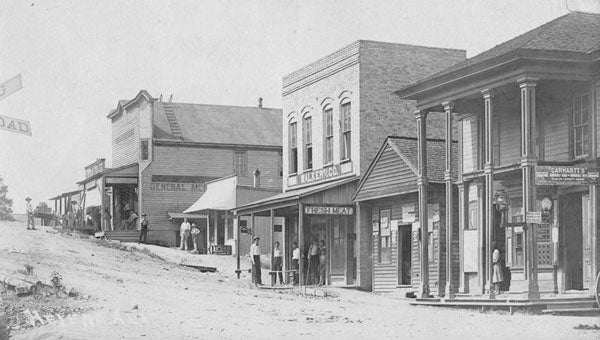

Helena's Main Street in 1910 housed a meat market, a milliner and a general mercantile to provide for the everyday needs of Helena's coal mining citizens. (Contributed/Ken Penhale)

By CHRISTINE BOATWRIGHT / Staff Writer

The cities and towns of Shelby County blanket the region with rich heritage. Cities, similar to their citizens, are forever changing, being forgotten and offering new opportunity. Since its inception in 1818, Shelby County has lost a handful of industrial hubs to progress and expansion of other thriving areas.

Shelbyville

Shelbyville was selected as Shelby County’s first county seat in 1820. The town was located in the historic center of Shelby County, in modern-day Pelham. Shelbyville held the county’s first courthouse, a log building costing $53 for construction.

Shelby County is older than Jefferson County, and as Jefferson, St. Clair, Talladega and Chilton counties were formed, Shelbyville was no longer the center, according to Bobby Joe Seales, president of the Shelby County Historical Society. In 1826, the county seat moved to Columbia, but since a “Columbia, Alabama” already existed, Shelby County’s Columbia’s name was changed to “Columbiana” in 1831.

Bridgeton

Bridgeton, now drowned under the waters of Lake Purdy off U.S. 280, was a farming community lost to progress. An article entitled “Bridgeton: A farming community beneath Lake Purdy” was written by Gary V. Pool, and is available from the Shelby County Historical Society. The article records the beginnings and ending of the community.

According to the article, after Andrew Jackson’s victory at Fort Jackson during the Creek War, his men traveled through the Cahaba Valley region looking for surviving Native Americans. In 1814, the war officially ended, and many of Jackson’s men returned to the Cahaba Valley to settle. And thus, Bridgeton was created.

The community was known for its rich farmland, but in 1906-1907, the city of Birmingham began to purchase land in the Bridgeton area. The erection of Purdy Dam and the creation of Lake Purdy caused Bridgeton to lose farmland to flooding and forced many families to move from the area.

Newala

The community of Newala was located on Shelby County 25 between Montevallo and Calera. It had a lime plant, and was formerly known as “Ganadarqua” or “Hales.” Its post office was created in 1893 and closed in 1943.

When the town was dissolved, its school was torn down and moved to become Pelham Elementary School. After Valley Elementary was built and Pelham incorporated, the old Pelham Elementary was used for city hall until a new city hall building was constructed on the site, according to Seales.

Newala's school was moved to Siluria in 1940 to construct Pelham Elementary School. The building later became Pelham's City Hall before being torn down to make room for Pelham's current city hall building. (Contributed)

A piece of wood from the original Newala school created the base of the game ball trophy — the trophy passed between rivals Pelham and Alabaster during football season.

Siluria

Another piece of the Pelham-Alabaster game ball belonged to the forgotten town of Siluria, located where the city of Alabaster stands presently. Wooden spindles on the game ball are from the Buck Creek Cotton Mill of Siluria.

The town of Siluria was once a bustling mill town. The town began when Thomas C. Thompson built the Selma Cotton Mill on the banks of Buck Creek in 1896, according to research conducted by Seales.

The Buck Creek Cotton Mill was located in Siluria in the late 1800s to early 1900s. The water tower is still standing in modern-day Alabaster. The Alabaster Senior Center was built on a portion of the mill's former foundation. (Contributed)

The mill was later renamed Buck Creek Cotton Mills in 1911. Reports from that time stated the town had a “good school, “a “good church” and the town was “in good shape,” “clean” and “healthful.” In 1921, the town built a four-room high school. The school was named after Thomas Carlyle Thompson, therefore it was the beginning Thompson High School.

“People can relate to Siluria,” Seales said. “So many of us can remember when it was here.”

Siluria flourished while the cotton mill was in good standing. On May 25, 1954, Siluria was incorporated with a population of about 600 citizens. In 1959, a company from New York purchased the mill operating facility, factory site and mill village property. The name changed to Siluria Mills, Inc.

In 1965, the mill’s name changed for the final time to Buck Creek Industries, Inc., and the mill village houses were sold to the employees. The operating facility and the factory site were sold in 1968, and the mill closed its doors in May 1979. The Alabaster Senior Center was built in 2010 where the Siluria cotton mill once stood.

Helena

Historic Helena looked quite different than present-day Helena. The city was settled before 1820 as a farming community, according to Helena historian Ken Penhale. During the Civil War, the railroad passed through the town. While the railroad was being built, a railroad engineer fell in love with Helen Lee, the woman who would become his wife. He named the town “Helena” in her honor.

Today's downtown Helena offers a different variety of businesses than when it was first founded in the early 1900s as a coal mining town. (Reporter photo/Jon Goering)

A gristmill was located on the river during the town’s early years, followed by a rolling mill in 1963. Workers in a rolling mill produced iron bars, cotton ties and steel plates for the Confederate Navy, Penhale said.

Coal mining in Helena started before the Civil War. Coke ovens are stone structures that miners put coal into for baking. Coke is a substance that makes iron; it’s used as a heat source. A section of coke ovens still stand near Buck Creek in Helena. The forgotten town of Hillsboro, just north of Helena, once held larger coke ovens in the 1870s.

In 1933, an F-4 tornado “tore up the town,” Penhale said. The tornado destroyed the town’s three churches, homes, the governor’s home and the gristmill.

“Quite a few people were killed. It scarred a lot of people,” Penhale added, “but not a lot of people left from the tornado.”

Mt Laurel

The 12-year-old community of Mt Laurel reflects a different era of Shelby County living. EBSCO, a privately held company with headquarters located off U.S. 280, broke ground on the planned community of Mt Laurel in January 1999.

“Certain things are required for small towns to work,” said Rip Weaver, current executive director of Aldridge Gardens and former Mt Laurel town landscape artist.“They need center walking paths and a discernible city or town center that supplies everyday needs.”

Weaver said all aspects of Mt Laurel are “very well managed,” and everyone knows everyone. The town’s planners even planned to implement street parking rather than attached garages to encourage neighbor interactions.

Visitors to Mt Laurel have trouble believing the community is new, as the planners worked to capture an old-town feel.

“We created something with instant age to it, like a forgotten town that was thriving,” Weaver said. “Mt Laurel looks the way it looks because it was programmed to be that way — It was ‘Disneyfied.’”

Modern-day Helena photos by Jon Goering. Mt Laurel photo contributed by Mary Peters. Black and white Helena photos contributed by Ken Penhale. Siluria photo contributed by Bobby Joe Seales. Illustration by Jamie Sparacino. Map by Christine Boatwright.